Bailee Hopkins-Hensley is passionate about exploring the connections that humans have to plants—especially the connections that indigenous communities have to the species that sustain them. She earned a BS in plant science in 2018 and an MPS in public garden leadership in 2019, but her interest in plants started many years earlier, when she was a child.

Growing up in a house full of plants

Her grandparents lived with the family for most of her childhood, and her grandfather loved plants. Hopkins-Hensley recalls his extensive gardens, both outside and in three rooms that were converted into a conservatory inside their Colorado home. He grew cacti inside and food plants outside. At the age of 12, she planted her first backyard garden.

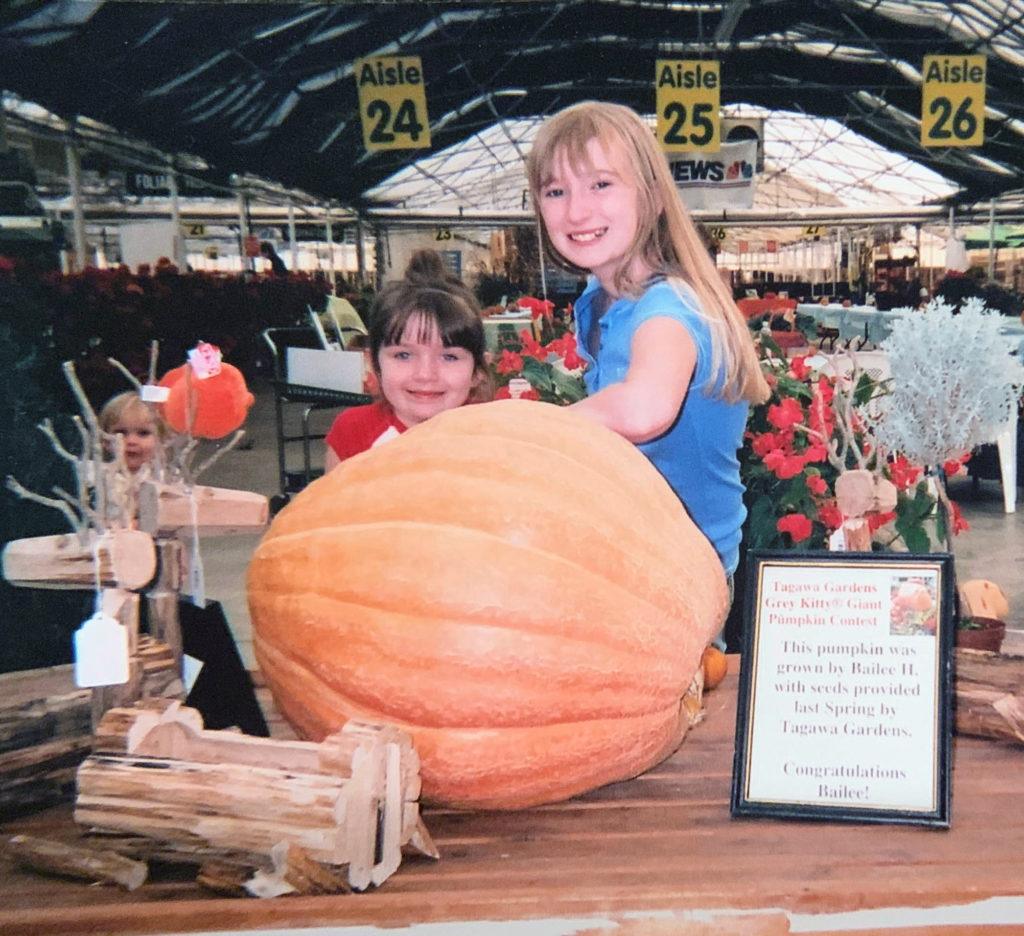

“I wanted to explore the types of plants that my ancestors from my mom’s side of my family had planted to sustain themselves,” says Hopkins-Hensley. “I became very interested in the Three Sisters cropping system and tried growing squash, pumpkins, and sunflowers.” Her love for gardening, and her garden beds, expanded from there—eventually leading her to Cornell.

Becoming a leader in her field

Cornell Botanic Gardens, in partnership with Cornell’s School of Integrated Plant Sciences’ Horticulture Section, offers a one-year Masters of Professional Studies degree program for individuals interested in leading botanic gardens and similar organizations. “The MPS gave me to opportunity to take courses that developed my leadership skills, such as a workshop in science communication, a course in non-profit finance and management, and a course in leadership theory and practice,” Hopkins-Hensley says.

All MPS students are required to complete a capstone project. Under the supervision of their faculty advisor, the students work on solving real-world problems. Hopkins-Hensley’s research focuses on the detrimental impacts of the Emerald Ash Borer, a non-native beetle, on native ash trees.

For her MPS capstone project, Hopkins-Hensley is mounting an exhibit to showcase the relationships that ash trees have with the world around them. The exhibit will be open from mid-July through December 2019 at the Nevin Welcome Center of Cornell Botanic Gardens.

The exhibit is designed to travel to botanic gardens across the United States. Hopkins-Hensley hopes that other public garden professionals can follow her lead and engage with local communities to create accurate interpretive exhibits that celebrate the value of native plants.

Celebrating native species

New York has about 900 million ash trees—all of which are threatened by the emerald ash borer. The borer larvae feed on the inner bark, which destroys the vascular system of ash trees and disrupts their ability to transport water and nutrients throughout the plant. The insects have already killed millions of ash trees and upset the complex relationships the trees have with their environment.

Healthy ash trees provide shade for understory plants, a food source for small animals, and nesting areas for birds. More than 150 species of butterflies and moths depend on ash trees as their host, and birds and other animals depend on these insect larvae for food. Ash trees help sustain wetlands across the Northeast and eastern Canada, and they play a significant role in sustaining indigenous communities in this region.

Our ash trees are more than just safety hazards.

“I wanted to show that—despite the impacts of the emerald ash borer—our ash trees are more than just safety hazards,” she says. “Ash trees have relationships with everything, from the insects and mammals they support, to the water and the plants that they live among, to humans.”

She hopes that by educating people about the role that plants play in supporting natural communities, they will be inspired to better “protect our Earth and the other beings that live among us.”

Hopkins-Hensley’s action project was inspired by a friend in the local Haudenosaunee community, who shared some of the challenges her community faces because of the emerald ash borer. Indigenous communities utilize black ash bark for their basketry, and the emerald ash borer threatens this practice and transfer of knowledge to the next generation. “The loss of ash trees will deeply impact North American Indigenous communities,” says Hopkins-Hensley.

Finding a place at Cornell

Hopkins-Hensley first learned about Cornell at the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma’s college fair, where she met Kathy Halbig, the student development specialist at Cornell’s American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program. “Her description of the diverse and welcoming community at Akwe:kon and in the student clubs, Native American and Indigenous Students at Cornell and the American Indian Science and Engineering Society, are what convinced to me apply,” she says.

She was also attracted by the opportunity to earn a minor in American Indian and Indigenous Studies. “I chose to attend Cornell because of the strong indigenous community—which was one of my top priorities when applying to colleges,” says Hopkins-Hensley.

Cornell’s financial aid offer sealed the deal. Grant aid and endowed scholarships covered the majority of Hopkins-Hensley’s costs to attend Cornell. “Without the financial assistance I was provided as an undergraduate, I might not have chosen to dive into the MPS right after graduating,” says Hopkins-Hensley. She received the Peter and Christine Ruppe Memorial Fellowship in Public Garden Management from Cornell to help cover the cost of her graduate studies, along with external scholarships from the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

During her undergraduate career, she worked as an intern at Cornell Botanic Gardens and at the Ithaca Children’s Garden. At the Botanic Gardens, Hopkins-Hensley discovered the native plants of the Cayuga Lake Basin. “I began to build my relationship with the plants that are native to the place that I was living in,” she says.

It’s so important to get to know the place where you are living and the people who live around you.

While at Cornell, Hopkins-Hensley has formed connections with the indigenous community at Cornell and with members of local indigenous communities. “The people I’ve met have helped me understand this place where I’ve lived for the past five years, and they’ve helped me understand myself as a Choctaw student and a visitor here,” she says. “It’s so important to get to know the place where you are living and the people who live around you.”

Promoting plant-people interactions

Later this summer, Hopkins-Hensley will start a new job at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation in Upperville, Virginia, as a gardener in their Bio-cultural Conservation Farm. Hopkins-Hensley hopes that one day she will have the opportunity to work in her own community, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and explore Choctaw knowledge of plants. Wherever she works, she wants to build bridges between public gardens and indigenous communities.

“In the long term, I want to play a role in respectfully developing native plant gardens that promote hands-on learning and plant interaction for people of every age,” says Hopkins-Hensley. “I also want to help Native American communities build their own community gardens, and help public gardens to interpret the cultural relationships surrounding their plant collections.”