David Strip ’77, PhD ’78 has lived in his adopted home of New Mexico for more than 40 years. Strip came to Cornell for graduate school, to study operations research (OR). “At the time, and to this day,” he says, “Cornell had one of the top-ranked, if not the top-ranked, OR department in the country.”

Strip said he felt academically unprepared for the rigor of Cornell. “Many of the other students were better prepared for the course of study,” he recalls. When asked what his biggest success was at Cornell, he laughs and says, “Well, I graduated!”

Recognizing any person

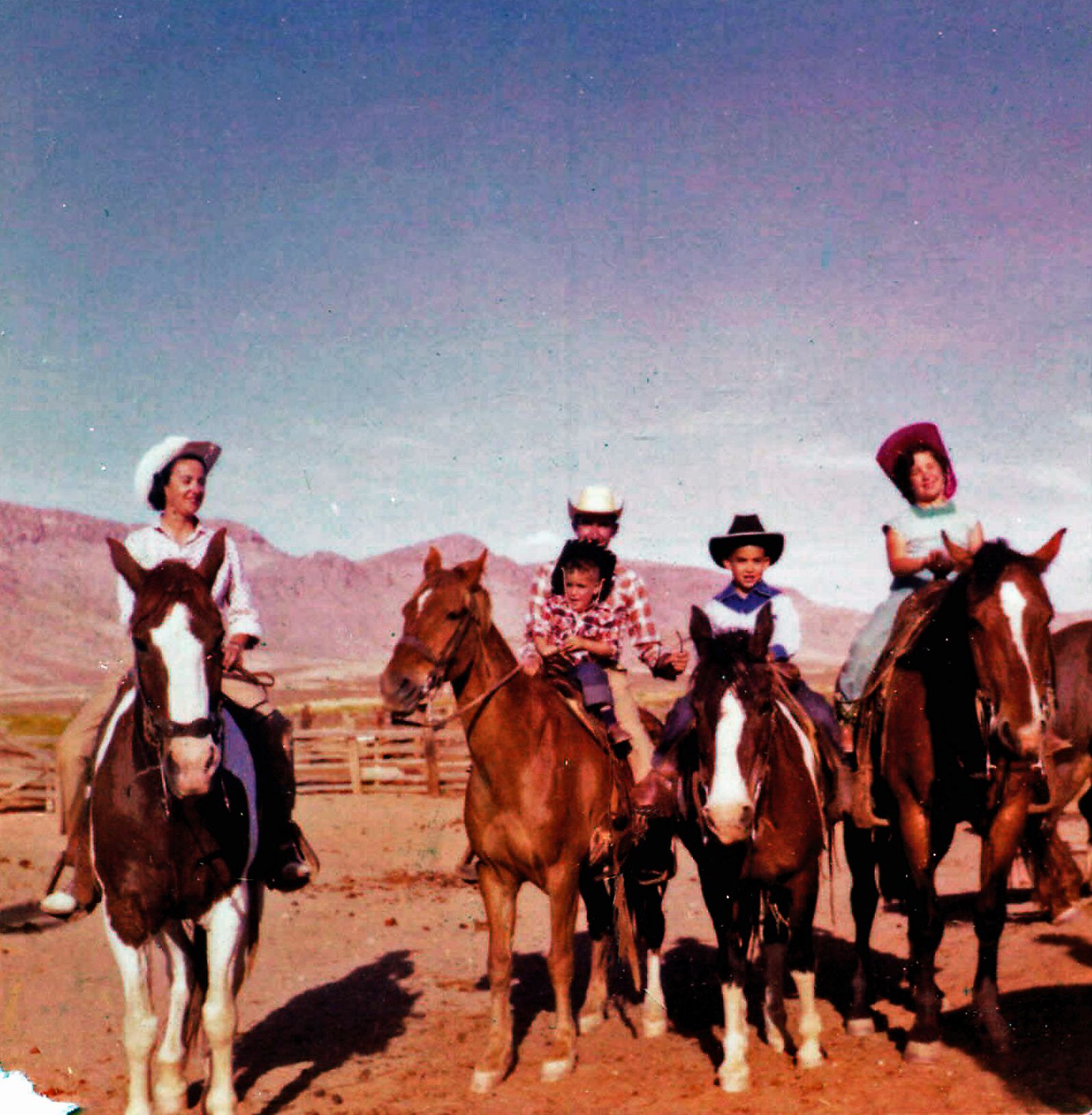

Strip’s parents were born in Antwerp, Belgium, and emigrated to the US during WWII, when they were teenagers. His father left Antwerp one day before the Nazi invasion, and he and his family spent about a year as refugees in France, waiting to secure visas to enter the US. Both his parents were Jewish and survivors of the Holocaust.

Strip’s parents attended college in the US, and his father was eventually drafted and sent to Camp Ritchie, a top-secret school that trained soldiers as interrogators and counter-intelligence agents. “As a Jewish refugee, his knowledge of foreign languages, especially German, and local customs made him invaluable,” Strip says. His father served as as a translator in the Nuremberg War Crimes trials.

Strip was raised with a “never again” consciousness by his parents, which Strip said extended not just to Jews, but to “any people.” After spending four decades living in New Mexico, Strip recognizes “the on-going impact of the literal and cultural genocide that resulted from the conquest of the [North American] continent.”

“New Mexico is my home and I feel an obligation to make it a better place,” he says.

I like to think… this gift has influenced others to re-think financial aid at Cornell.

Building social capital

Becoming a Cornellian automatically connects graduates with an extensive network of more than a quarter million alumni, and Strip believes that access to this network makes all the difference. “Just having a Cornell degree makes you a member of a network that eagerly reaches out to younger members with job opportunities, connections to businesses, financing, etc., that they might not make available otherwise,” he says.

Cooperation among Cornellians was the key to Strip’s success when he faced the challenges of the rigorous OR curriculum as a graduate student. He turned to his fellow students for academic and moral support, and he credits his OR study group for helping him to succeed at Cornell. “Each of us had some topics that we understood and others we struggled with, so each person led in the areas they understood best and followed where others were stronger.”

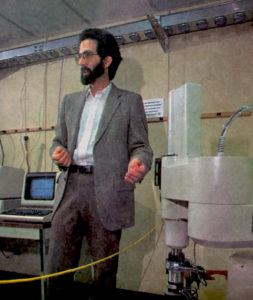

In the years after graduation, about half of the members of this study group went on to work with Strip at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque. “There is no doubt that a Cornell degree carries a cachet that opened doors for me,” he says. Strip spent the next three decades working at Sandia Labs, where he worked in R&D management, modeling and mathematics, and massively parallel computing. He has a dozen patents across a variety of domains.

Strip shared some words of wisdom for current Cornellians. He advises every student to take at least one course outside their comfort zone. He reminds business and engineering students that, “written communication skills are more important than you think.” And he reminds liberal arts students that, “numeracy is as important as literacy.”

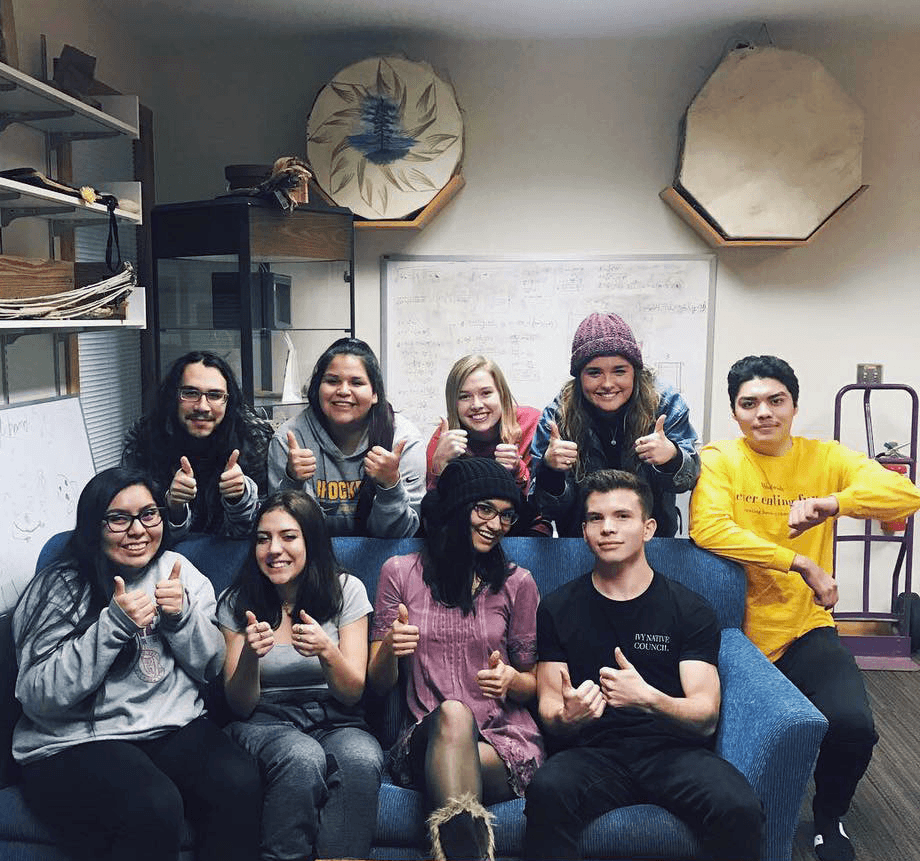

Filling an unmet need

In 2018, after working closely with Joe Pesaresi and Ian Garrett in Alumni Affairs and Development, Strip made a gift to establish a fund to support students in the American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program (AIISP) at Cornell. “Cornell is one of the few Ivy-Plus institutions that has an indigenous studies program,” says Pesaresi, a major gifts officer at Cornell. AIISP provides a unique combination of American Indian and Indigenous Studies courses and student leadership opportunities, and Akwe:kon, the first Native student residence hall in North America.

Strip had a unique purpose in mind for his gift: “to provide an opportunity for Native American students to develop assets to survive, and hopefully thrive, in the world they have been forced into.” The fund Strip established is intended to help Native students build social capital, which he defines as “that collection of knowledge, relationships, and connections that allows some to succeed where others don’t.”

I wanted the money to pay for a winter jacket that could survive an Ithaca winter and look like the jackets the other kids were wearing (if that’s what the student wanted).

The fund fills in the gaps that traditional financial aid does not cover and enables students to mix with their peers on a more equal footing. It provides support for indigenous students to attend conferences and cultural events, to travel home or have visitors from home, and to purchase clothing to survive the Ithaca winter. He explains that many Native students have never traveled more than 50 miles from home, and those from the Southwest come from a climate where “two days without sunshine is unthinkable.” Students from remote areas of a reservation may not have phone or Internet access to their families—making the prospect of attending Cornell both a long and a lonely journey.

“I wanted the money to pay for a winter jacket that could survive an Ithaca winter and look like the jackets the other kids were wearing (if that’s what the student wanted),” Strip says. “I wanted our students to be able to afford a summer internship without worrying that they should have been working back home at some minimum-wage job over the summer.”

Strip’s big-picture vision is that the fund will “offer students the chance to develop the confidence and social skills for dealing with a society that has placed them at a disadvantage, and to engage with that society without compromising their values and beliefs.”

Driving the evolution of financial aid

Since retiring from the Labs, Strip has volunteered his time as a site steward for the Santa Fe National Forest, as a board member for the Hopi Education Endowment Fund, and as an on-call scientist for the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) Human Rights Program. He is motivated to make a positive impact in his community and for the people who live there.

Strip hopes that his giving to Cornell will help to shift the conversation to include the full range of financial needs of indigenous students. “I wanted my gift to supplement existing funding to fill the gap that had not been previously acknowledged,” he says.

If you believe Cornell can do better, think about how you might use a gift to guide Cornell to improve its performance.

Strip believes that donors like him are helping Cornell to evolve. “I like to think this gift has influenced others to re-think financial aid at Cornell,” he says. “Those who share this new viewpoint are helping me to spread that idea, in hopes that others will make similar contributions to better support communities that otherwise can’t afford Cornell.”

Strip has pledged a legacy gift to sustain his fund, and he is hoping that his giving can inspire others to give to the area they care most about. “If you believe Cornell can do better, think about how you might use a gift to guide Cornell to improve its performance. You may be as surprised as I was at how responsive Cornell can be to your suggestion (and for less money than you think!),” he advises.

“I can’t begin to describe the pleasure I receive knowing that I’ve changed the future of Cornell in a direction I care about,” he says.