Yet ever the green hills stay

To blaze in the west-waning day.

—From the poem “Immortal at the River” by Yang Shen (1488-1559), translated by Moss Roberts

Elizabeth “Betty” Miller Francis ’47 touched many lives and organizations through her philanthropy and passion for travel, the outdoors, and art. With her giving, she supported galleries and music, ecological research, and natural habitats for zoo animals.

In her adopted hometown of Colorado Springs, she gave to the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College, Broadmoor Church, and Cheyenne Mountain Zoo. At the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center Betty funded the Mashburn/Marshall Tactile Gallery, named after the mother of her dear friend and colleague docent, to bring art to the sight impaired. Betty’s support of the Broadmoor Church established, among other things, a youth choir to cultivate in others a love a music that can last a lifetime.

At Cornell, her bequest now brings researchers into the wild and the community into the museum.

Journeying from Cornell to Colorado

Although she spent most of her adult life in Colorado, Betty was born in Watertown, New York, into a family with strong connections to New York State and Cornell.

Family Cornellians include: Betty’s parents Sara Speer ’21 and Peter P. Miller Sr. ’18; uncle, Franklin Speer ’21; brothers Richard “Dick” S. Miller ’56, MBA ’58, and Peter P. Miller Jr. ’44, MBA ’48; niece Christina Miller Sargent ’73 and nephew-in-law David C. Sargent ’73; and grandnieces Anne Miller Sargent ’04, Elizabeth Cutler Sargent ’05, and Morgan Alexis Miller ’07.

According to Dick, their parents Sara and Peter Sr. met on a blind date at Cornell for an activity that might send a shudder through today’s student services staff: tobogganing. Sara’s arm was “hurt a bit,” in an encounter with a tree or a post but the visits Peter Sr. paid her during her convalescence soon “started the thoughts of getting married,” says Dick.

These organizations were her children.

After graduating from the College of Arts & Sciences in 1947, Betty left for New York City and a career in the travel industry. After she and John Francis married in the late 50s, they saw a move to Colorado as an adventure. Travel remained a life-long passion and her many safari trips gave Betty an appreciation for animals in natural habitats and for the broad expression of art in human habitats.

After John’s death in the late 1970s, she turned her passions into supporting many local organizations, including the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo. At a time when many zoos were reconsidering their created environments, Betty helped the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo develop and fund a reconstruction into naturalistic habitats. In 2011, the zoo named a giraffe “Betty Francis” in her honor.

Turning back to Cornell

Betty’s family helped to make sure her bequest would support the things she loved. Elizabeth “Beth” Miller, spouse of Dick and expert in estate law, worked with Cornell staff to direct her giving. “We got to talking about what she was thinking,” says Beth. “These organizations were her children.”

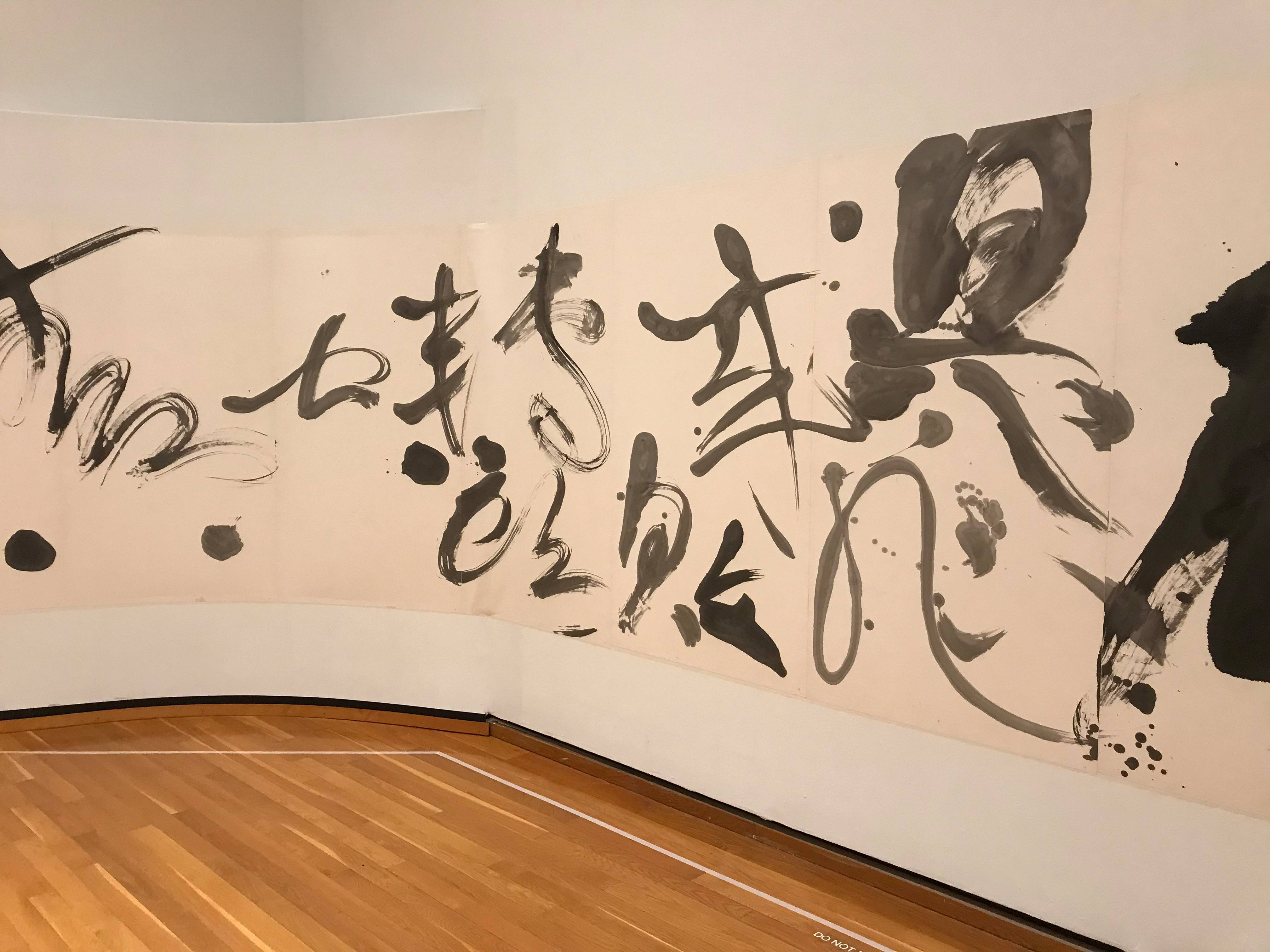

Betty had a strong relationship with the former Richard J. Schwartz Director of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Frank Robinson, who helped evaluate her collection. Today, her bequest supports an annual exhibit at the Johnson Museum including the current Tong Yang-Tze: Immortal at the River, a 54-meter long calligraphic work filling the gallery space and depicting a famous poem by Yang Shen (1488-1559). “One of the aims [of the fund] was to have the income so that they could go outside the museum to get pieces they wouldn’t necessarily have in their permanent collections,” says Dick.

International loans of contemporary art “can be costly in terms of shipping and special installation needs, but we want students to have the opportunity of seeing great works that would otherwise not be available to them,” according to Ellen Avril, chief curator and curator of art. In the case of Tong Yang-Tze: Immortal at the River, “we installed a system of temporary walls using new construction to blend corners seamlessly so the work spirals into the center of the gallery,” says Avril, “It looks like it’s always been there.”

Having an endowment fund to support exhibits is really critical.

The Tong Yang-Tze exhibit was co-curated by An-Yi Pan, associate professor in the Department of the History of Art and Visual Studies, “with connections to the curriculum and opportunities for collaboration with other Cornell units in mind,” says Avril. “Cornell students of dance, under the direction of instructor Jumay Chu, devoted a piece in their Locally Grown Dance concert—one of the last before the university closed—to performing with large video projections of Tong’s [calligraphic] characters as the backdrop, the dancers echoing the forms of the brushstrokes.”

“The Elizabeth Miller Francis ’47 fund can support different aspects of an exhibition, such as partnering with another museum on a traveling exhibition and/or producing an exhibition publication, as with the 2017-18 exhibition Lines of Inquiry: Learning from Rembrandt’s Etchings, co-organized with the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College. The exhibition catalogue was recognized for its scholarly contributions with awards from both the College Art Association and the International Print Dealers Association.

“Having an endowment fund to support exhibits is really critical,” Avril continues. “It is something we can count on each year, gives us flexibility and nimbleness to respond to opportunities, and even if there are future budget cuts or less endowment payout, the restricted use of this fund means we can mount exhibits not only in good times, but in bad.”

The fund has supported six exhibits, almost one per year, since its inception. The first, Food-Water-Life/Lucy+Jorge Orta, explored the artists’ interests in biodiversity, environmental conditions, climate change, and exchange among peoples.

Bringing researchers into the wild

Betty’s love of travel in the natural world fostered a passion for animals in their environments and the protection of our planet. Her family knew that Betty appreciated what the experience of travel could do for those who have not travelled much beyond home or Cornell. To translate these loves into Cornell support, staff hit upon the idea of introducing the family to the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and research travel.

Today, the Elizabeth Miller Francis ’47 fund for Ecology and Evolutionary Biology supports undergraduate and graduate students working together in research fieldwork.

“Graduate students apply for the funding in the spring,” says Jeremy Searle, chair of the department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, “and the funding supports an undergraduate working with the graduate student.” Because it funds both the graduate work and undergraduate opportunity, “it’s a remarkably good way of using funding,” he says.

There’s something different, dramatic, and incredibly urgent about working in a stunning and raw field site that is exposed to rapidly changing conditions.

“The graduate student cohort has expertise in a field study system. They’re a little bit older and mentor the undergraduate students,” according to Searle. The undergraduates benefit from that mentoring, and the work and partnership “fires the enthusiasm of the undergraduates” to pursue additional fieldwork and research.

“Ecologists are biologists interested in the natural environment and evolutionary biologists study changes through time that result from selective pressures in the natural environment,” he explains. “In terms of personal development, [field work] is a tremendous thing. Just being outdoors, working with others, and working as a team helps people grow and solve problems together.”

“And, it’s a real leveler: When you’re out in the field, you don’t have hierarchy. You’re all mucking in and you need to work as a strong team, to benefit from ideas and things that everyone is spotting. When you have these pairs—the undergraduates, as they are learning, are really contributing,” says Searle.

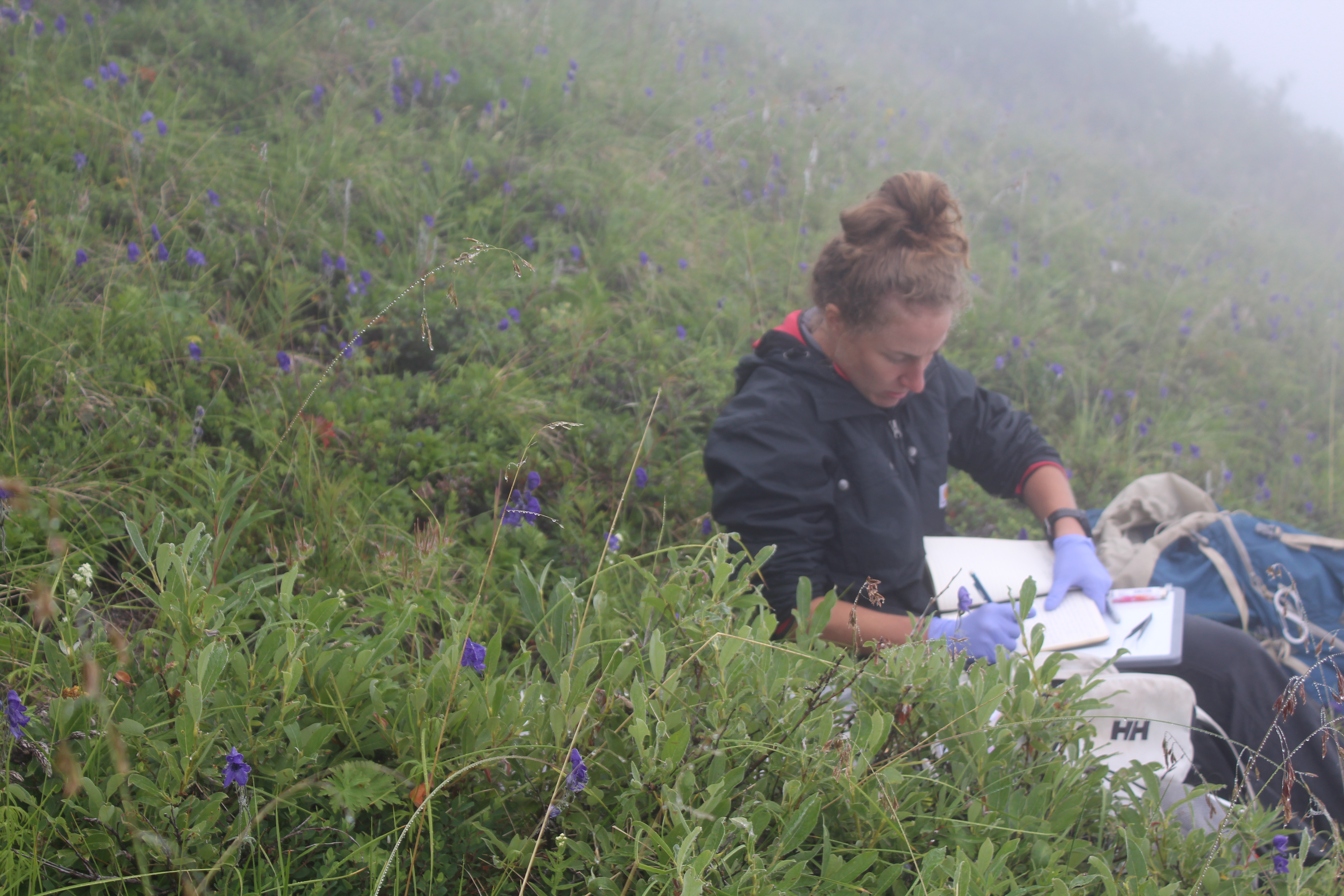

Elizabeth Lombardi, a doctoral student in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology studies plant virus diversity. She was able to use the Elizabeth Miller Francis fund to hire a field assistant, Emily Shertzer ’16, to travel to Alaska’s backcountry.

“We searched for the northernmost populations of a plant host species, Boechera strica, in Denali and Wrangell-St. Elias National Parks. We collected tissue, seeds, coordinates and phenotypic data. RNA extracted from the tissue samples will provide insight into the diversity (or lack-there-of) of viral associations across the full host range.”

“Emily and I also learned a great deal about backcountry river crossings and Grizzly bear safety, black flies, and sleeping under a midnight sun!”

“Conducting fieldwork in Alaska reminded me of what I’m working so hard to understand and protect,” says Lombardi. “Luckily, I’ve always had easy access to wild areas…but there’s something different, dramatic, and incredibly urgent about working in a stunning and raw field site that is exposed to rapidly changing conditions.”